For decades, scientists have debated whether humanity is an extraordinary, one-in-a-trillion accident or simply the natural result of evolution given the right conditions. A new study challenges the long-standing “hard steps” theory, suggesting that intelligent life may not be as improbable as previously thought. Researchers from Penn State argue that rather than requiring a sequence of nearly impossible events, the emergence of intelligent life on Earth—and possibly on other planets—could be a predictable outcome of planetary and biological evolution.

The “hard steps” model, proposed by theoretical physicist Brandon Carter in 1983, suggests that the evolution of intelligent life was an extraordinarily rare event, occurring against near-impossible odds. Carter‘s argument was based on the fact that it took billions of years for intelligent life to emerge on Earth, roughly half the lifespan of the Sun. If intelligence were common, he reasoned, it should have developed much sooner. This model has shaped the way many scientists think about extraterrestrial life, leading to the assumption that humanity may be alone or nearly alone in the universe.

However, the new study, published in the journal Science Advances on February 14, presents an alternative perspective. The research team, including geobiologists and astrophysicists, suggests that Earth‘s environment has played a crucial role in shaping the evolution of life. Instead of being a matter of luck, the development of complex organisms may have been dictated by the gradual opening of “windows of habitability.”

One of the key arguments in the study is that Earth‘s early environment was too harsh for complex life to develop. Over time, however, conditions improved—oxygen levels rose, climate stabilized, and essential nutrients became more abundant. These changes, driven by geological and biological processes, set the stage for evolutionary advancements. Dan Mills, lead author of the study and postdoctoral researcher at The University of Munich, explains that Earth‘s oxygenation was a turning point. The rise of photosynthesizing microbes increased atmospheric oxygen, which, in turn, allowed for more complex multicellular life to thrive.

“We’re arguing that intelligent life may not require a series of lucky breaks to exist,” Mills said. “Instead, it emerges when the conditions are right. Humans didn’t evolve early or late in Earth‘s history—we evolved ‘on time’ when the environment was finally suitable.”

This viewpoint contrasts sharply with the “hard steps” theory, which suggests that intelligent life is an anomaly. Instead of being a cosmic accident, the study proposes that human evolution was the result of Earth‘s environment becoming progressively more hospitable. If this pattern holds true for other planets, it increases the likelihood that intelligent civilizations exist elsewhere in the universe.

The study challenges the core assumption of the “hard steps” model: that evolution is constrained by the lifespan of a planet‘s star. Instead, the researchers argue that the timescale of life‘s evolution should be measured in geological terms. Earth‘s changing climate, chemistry, and biological diversity all played a role in determining when complex organisms could emerge. According to Jason Wright, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at Penn State and co-author of the paper, the gradual evolution of life is an expected process rather than an improbable event.

“We’re taking the view that life evolves with the planet,” Wright said. “It moves at a planetary pace, shaped by environmental conditions rather than a cosmic lottery.”

Part of the reason the “hard steps” model has persisted, the researchers say, is that it originated from astrophysics, a field primarily concerned with the formation of stars and planetary systems. However, this new study bridges the gap between astrophysics and geobiology, creating a more holistic view of evolution. By incorporating insights from both disciplines, the researchers present a compelling case for why intelligence may not be a cosmic fluke.

“This paper is an incredible act of interdisciplinary collaboration,” said Jennifer Macalady, professor of geosciences at Penn State and co-author of the study. “Astrophysicists and geobiologists have traditionally approached these questions from different angles, but by combining our knowledge, we’ve built a new framework for understanding the evolution of complex life.”

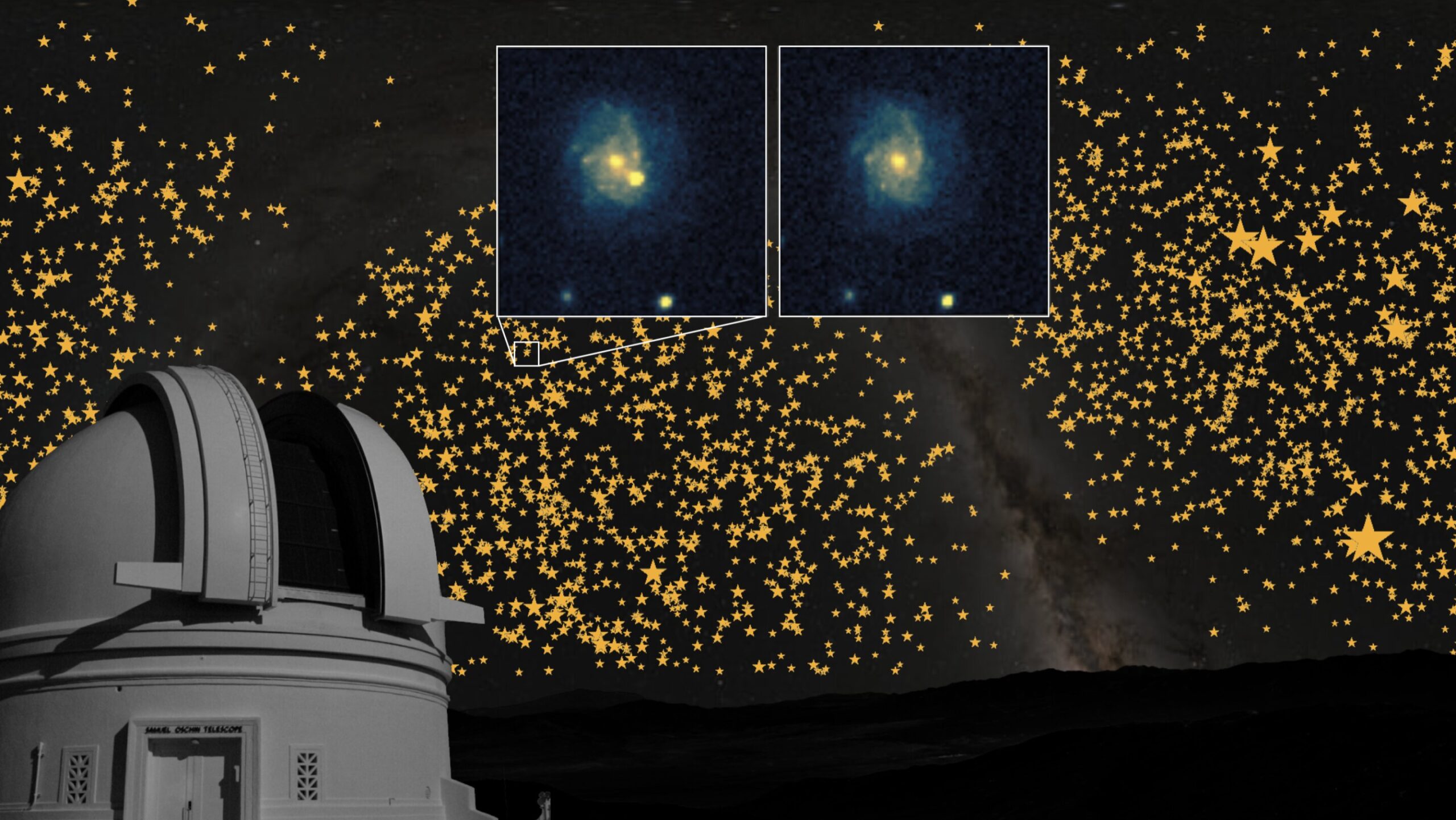

To test their model, the researchers have outlined several future studies. One approach involves searching for biosignatures—chemical signs of life—in the atmospheres of exoplanets. If oxygen, methane, or other life-related compounds are detected on distant worlds, it could support the idea that life follows a predictable trajectory. Another approach involves experimental studies on simple life forms, testing how environmental conditions influence their ability to evolve into more complex organisms.

Additionally, the researchers propose revisiting Earth‘s own evolutionary history. They suggest investigating whether key milestones—such as the emergence of photosynthesis, the rise of multicellular life, and the development of intelligence—could have occurred multiple times but were erased by extinction events. If evolution repeatedly produced similar innovations, it would further support the idea that intelligence is an expected outcome of planetary evolution rather than a statistical anomaly.

“Instead of a series of improbable accidents, our framework suggests that evolution unfolds as conditions allow,” Wright said. “If similar conditions exist elsewhere in the universe, intelligent life may be more common than we previously thought.”

The implications of this research are profound. If intelligence is not a rare cosmic accident, then the search for extraterrestrial civilizations becomes even more urgent. Scientists may need to rethink their strategies for finding life beyond Earth, focusing not just on planets that resemble early Earth, but also on those that are undergoing environmental shifts that could foster the emergence of complex organisms.

While the debate over humanity‘s place in the universe is far from settled, this study offers a fresh perspective—one that challenges the idea that we are alone. Instead of being an extraordinary outlier, intelligence may simply be what happens when a planet‘s conditions align. And if that’s true, then the cosmos may be teeming with life, waiting to be discovered.

More information: Daniel Mills, A reassessment of the “hard-steps” model for the evolution of intelligent life, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ads5698. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ads5698